Silently taxing savers: Will inflation be the solution to today’s wartime levels of debt?

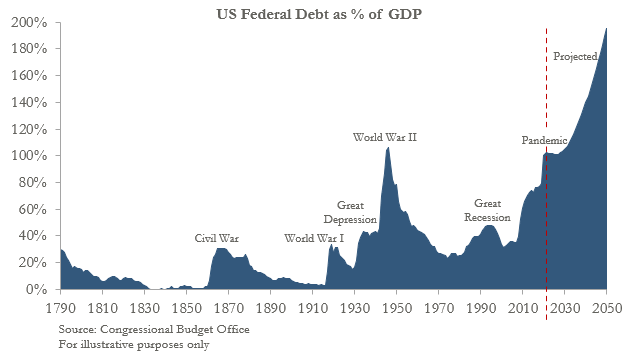

To say that government debt levels are high is nothing new. Even before Covid-19 hit, despite years of austerity, debt levels were already extremely elevated. But after the fiscal damage of Covid-19, debt as a percentage of GDP has now reached extraordinary levels that, when viewed from a long-term historical perspective, are jaw-dropping. Take the US, for example. Not since the end of World War II have debt levels been as high, and on current projections they are expected to skyrocket from here.

Few would argue that, in the wake of a global pandemic, extraordinary government spending was not justified. However, that does not change the fact that this debt must be repaid. The question for investors is how.

Looking at the debt situation coldly, without thinking about what is fair or morally right, there are ultimately only four ways to reduce government debt to GDP:

Default on your debt

Outgrow your debt

Raise taxes and/or cut spending

Inflate the debt away

Clearly, default is untenable for major developed economies. We can also discount the second option, which is typically based on hope rather than realism, not least because very high levels of debt are associated with lower rates of growth. The third, higher taxes and/or spending cuts, is likely to play some part, but in the current environment, after the years of austerity which followed the GFC, there seems to be little appetite for further large cuts to public spending. Meanwhile, substantially higher taxes are always politically difficult, and even sharp hikes in headline tax rates will not raise the amounts that are necessary. For example, according to a recent op-ed in the Financial Times, raising UK corporation tax from 19% to 24% would theoretically raise the equivalent of 0.7% of GDP – a drop in the ocean.

This leaves us with the final option which, coincidentally, is the one taken the last time government debt was at levels like today’s: the period after World War II. According to a 2015 IMF Working Paper[1] by economists Carmen Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia, in the period between the end of WWII and the 1970s, advanced economies managed to reduce government public debt from over 90% of GDP to less than 30%, by allowing higher inflation to persist whilst exerting control over nominal interest rates – a practice referred to as ‘financial repression’. Financial repression can take different forms, but its key pillars are:

Explicit or indirect caps or ceilings on interest rates (e.g. central bank buying of longer dated debt to keep interest rates low)

The creation of a captive domestic audience of domestic buyers through capital controls or prudential regulatory measures (e.g. compelling insurance companies, banks, or pension funds to hold a certain amount of their assets in domestic government debt, despite negative real yields).

Controlling lending either through direct ownership of banks or moral suasion.

In the presence of inflation, financial repression would see nominal interest rates held artificially low so that real interest rates are negative, which over time has the effect of lowering government debt levels. Alternatively, real rates are positive but still artificially lower than the rates governments would ordinarily have borrowed at, thus imposing a financial repression ‘tax’ on debt holders.

Of course, to accomplish this, governments and central banks must first generate the inflation needed, and in recent years this has been easier said than done. Factors such as globalization and rapid technological advances have proven to be formidable headwinds, depressing the prices of goods and wages, and thwarting central banks’ efforts. Even the act of ‘printing money’ through QE after the 2008 financial crisis failed to achieve inflation, despite many warnings at the time that these unconventional measures would lead us down a path of Weimar-style hyperinflation.

However, there are some reasons to believe this time could be different.

In the post-2008 era easy monetary policy was offset by fiscal austerity. This time, however, fiscal a

nd monetary policy are both pulling in the same direction. The numbers are also astronomical. Even former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, an influential Harvard economist and policymaker, who for years has argued for more reliance on active fiscal policy, expressed concern that what is being done is “substantially excessive”, calling it the “least responsible fiscal policy in the last 40 years”.

This extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus comes at a time when households have accumulated large savings during lockdown and, as economies are reopened, are expected to greatly increase spending.

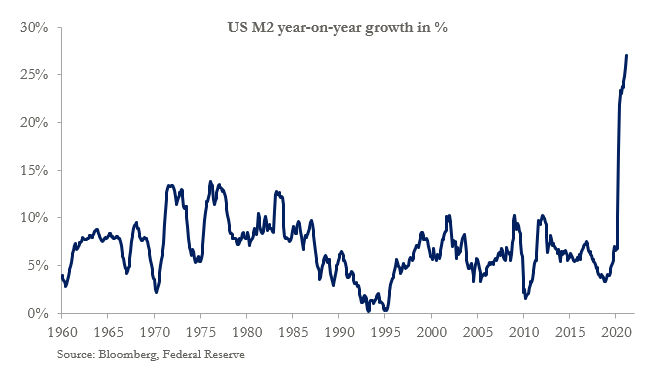

Governments have succeeded – where repeated rounds of QE failed – in sparking rapid growth in broader money. This is illustrated by the chart below, which shows so-called M2 in the US, representing not just by physical money in circulation, but also balances in checking accounts, short term time deposits, and retail money market funds. This growth was achieved through the various government credit guarantee or subsidy schemes, examples being the Paycheck Protection Program in the US, the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme in the UK, or the Coronavirus SME Guarantee Scheme in Australia. In a modern fractional banking system, it is commercial banks, not central banks, that really create most ‘money’, through lending. And where QE failed to convince banks to lend, government credit guarantees have succeeded.

Finally, central banks have recently made it clear that they are willing to risk inflation overshooting their targets to make up for years of below-target inflation. For example, in 2020 the US Fed, in a major shift of policy, changed to an ‘average’ inflation target over a cycle (without defining the horizon). Meanwhile, the RBA has insisted it will not raise rates until it sees wage growth sustainably above 3%.

Whether or not central banks will succeed in generating sustained inflation, after failing to do so for over a decade, is unclear. However, if they do, it seems likely that the solution to today’s wartime-like levels of debt will be very same strategy that was used in the post WWII period – a silent long-term tax on savers.

Miles Staude of Staude Capital Limited in London is the Portfolio Manager at the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.

[1] The Liquidation of Government Debt, IMF Working Paper, Carmen M. Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia, 2015